For those of you who aren’t familiar, in 2000 a man named Robert Putnam came out with a book titled “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.” In that book he asserted that community participation in the so-called “third space,” defined as any gathering place for people that wasn’t work or home, was dying.

Rotary clubs, churches, parent-teacher organizations, neighborhood councils, civic action groups, Scout troops, community gardens, and yes, bowling leagues, were all slowly losing members. Snared by television and the internet, isolated in suburbs, and atomized by choice, Americans were slowly becoming loners, incapable or uninterested in devoting time and energy towards social and cultural communities.

Putnam’s argumentative pièce de résistance was the aforementioned bowling league. Membership in bowling leagues had been on the downward trend, but the number of people bowling alone was steadily increasing. Putnam used these examples to hypothesize that the entire nation was experiencing a mass decline in social capital, leading to disintegrating ties between neighbors, communities, and society.

And although Putnam mostly kept his analysis contained to communities that require membership, it doesn’t take a genius to recognize this pattern in all third spaces. Shopping malls are at about half the capacity that they used to be, restaurants are empty on weekdays, and movie theaters are abandoned when 9 figure marketing budgets aren’t deployed. Smartphones are doing to public transportation what cars did 50 years ago, further separating us from the people around us. Dog parks are for sitting on a bench on your phone while Spot flirts with a labradoodle, not talking to people. And keep in mind, all of this stuff was already happening pre-covid. A year or so of lockdowns has put this phenomenon into overdrive, forcefully splitting us apart, and the siren song of algorithmically catered content filling the gaps.

The consequences of this shift are glaringly apparent. Articles, think pieces, and mildly unhinged Twitter/X rants abound on how lonely Americans are, how disconnected and angry and confused the world has become. I’ve lost track of the number of TikTok’s I’ve seen of parents or teachers bemoaning the fact that kids seem to have no in-person social skills whatsoever. Additionally, studies I’ve come across indicate that around 30 precent of men and 20 percent of women in America don’t feel like they have a single friend that they could talk to if they were having a hard time.

And you know what? They have a point. It’s true that we’re in more dire social straits than we probably ever have been. But this analysis isn’t the full picture.

As it turns out, the thing that Robert Putnam and plenty of others had predicted would kill off community, might just end up saving it.

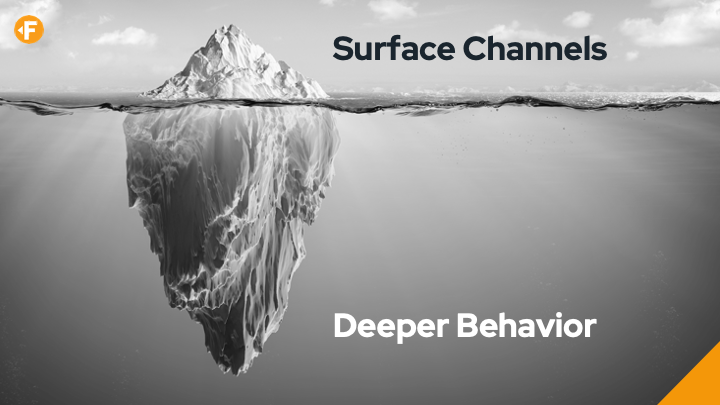

Putnam was right when he wrote “Bowling Alone”, and he continued to be right about the atomizing effects of technology for a good ten or so years. In some senses he still is right if what you’re doing on the internet is limited to things like doomscrolling Twitter and ordering food on DoorDash. But generalizing the effects of online life based off of just what the biggest, most marketing-driven apps are pushing is like scooping up a handful of seawater and using that sample to claim that there are no fish in the ocean.

We always have to look deeper than that, and when we do, we realize that underneath this digital surface is an ecosystem bigger, more vibrant, and above all, more organized than anything we’ve ever seen before.

Remember Minecraft? That blocky retro building game that took the internet pop culture world by storm about seven years ago? While it may have mostly faded from public view, today Minecraft has about 500,000 custom servers, game worlds that are all hosted and managed by players. And in these Minecraft worlds, players do more than just mine. They form actual functioning in-game governments. Propose and pass laws. Sanction rulebreakers. Hold festivals and memorials. Form factions and political parties. Go to war. Build planned communities and write neighborhood charters. Even develop basic economies, complete with currencies and exchange rates.

Minecraft isn’t even the biggest example. Roblox has literally millions of user-generated games and a daily player count of roughly 70 million users. There are roleplaying servers where people just pretend they’re living normal, everyday lives in a pixelated version of the modern world. There are co-op games, teamwork and survival games, exploration games, all of them with their own devoted player bases who, if they show up in those specific games enough, will naturally get to know each other and form bonds. Just like what would’ve happened at the average neighborhood community meeting 50 years ago.

“But your point only applies to video games!” you say, clutching your flat white and overpriced croissant, blissfully unaware of the overwhelming scale and labyrinthine extent of the internet. “Not so!” I reply. The most commonly watched genre of content on Twitch is “Just Chatting,” where thousands of streamers do nothing but talk to their followers, watch things together, and hang out. And those followers talk to each other as well, especially within the livestreams of smaller creators where the chances are higher that they’ll interact with the same people when they tune in.

Then of course, there’s Discord. Along with Reddit, Discord is one of the two current reigning champions of online community, and it’s earned this distinction not only for its popularity but its mind-boggling breadth of content. There are Discord groups for everybody from hardcore truck simulator players to med students to sports betters to drug users. Nearly every popular fandom has a Discord for itself. Plenty of Discord servers (usually just referred to simply as “Discords”) aren’t themed at all, they’re just organically grown groups of people that like to talk to their friends while they play games or browse the internet.

I’m a member of a Discord like that. When I was in high school I joined an online multiplayer Minecraft world and got to know someone who invited me to their server. Fast forward a decade, and I’ve grown to love these people. I’ve watched movies with them, played Dungeons and Dragons with them, and even gone to see two of them get married. We talk late into the night about politics, internet culture, and the games we’re playing. Or sometimes, we don’t talk at all. We do our own things like playing single-player games or browsing the web, but while remaining in voice chat. Just like a group of friends hanging out in their living room, reading, or scrolling their phones, occasionally breaking the silence to share something funny or exchange thoughts.

There’s a new kind of Third Space now: The Digital Third Space.

It’s the EVE online universe, the Subreddit, the World of Warcraft Server, the Twitch Chat, the Roblox game, the Minecraft world, the special interest forum, and the Discord server. It’s not precisely the same shape as the physical one. It obeys different laws and has different requirements. There are different subtypes and different push and pull factors than physical Third Spaces. We’ll go into those in subsequent articles. But the thing that matters is that they exist.

There may have been a broad decline in physical human social interaction; a weakening of bonds and fraying of ties among our neighbors as it becomes more and more possible to go about your day without talking to a single other human being. But with every system rendered outdated by advancing technology, a new one takes its place, and that’s precisely what’s happening to the Third Space. People of all ages, races, genders, nationalities, and cultures are flocking to the online world and building their social relationships there. The same processes that have always happened are happening now, just slightly out of view.

My last point is an important one. It may be tempting to disregard those hundreds of millions of people as a strange, disconnected subset of humanity. To look down on them as being socially inept, uneducated, unproductive, or abnormal. This is false. They are your neighbors, roommates, and work colleagues. They buy things, vote, go to the doctor, listen to music on Spotify, etc. just like the rest of us. Some of them probably even buy flat whites and overpriced croissants.

As marketers, advertisers, and researchers, we should never lose sight of the fact that there are millions and millions of people who find themselves most comfortable online – who would prefer to voice their thoughts, fears, desires, needs, or regrets in a Reddit thread or through a mic on Discord. And they deserve to be listened to. As a matter of fact, they must be listened to. There’s too much economic productivity wrapped up in them to not listen to them. At this point it’s just bad strategy not to.

As this phenomenon continues to develop, it will evolve and grow, branching even farther out than it already has. Maybe Mark Zuckerberg is right and sooner or later we’ll be virtual avatars, taking meetings in the Metaverse. Maybe super intelligent AI’s will run the whole thing, sorting, and connecting communities according to their own whims. I’m not sure.

But what I do know for sure is that this new medium of virtual community, supported by a vast network of digital Third Spaces, is here to stay. And we all need to start paying attention or get left behind.

Tony Fahmy

Tony Fahmy is an American freelance strategist, researcher, and world traveler. He’s currently based in Romania, but can be found in every corner of the world, learning, exploring, and documenting the many forms of this incredible thing we call humanity.